Looking Over the President’s Shoulder

When Alonzo Fields accepted a job as a butler at the White House in 1931, his plan was to work there for the winter. That winter lasted 21 years. Based on the real-life story of the grandson of a freed slave who grew up in an all-black town in southern Indiana, Fields is forced by the Depression to give up his dreams of becoming an opera singer and accept the job at the White House where he quickly was appointed Chief Butler. Looking Over the President’s Shoulder is told from the unique perspective of the Chief Butler who served four U.S. presidents and their families. Credit dramaticpublishing.com

Alonzo’s Stories

WVUT/WTTW First City Focus Program – Vincennes PBS

Focusing on topics and events of interest to our local area: Each week we invite you to take a closer look at the people, places and undiscovered stories in your community, as well as topics, events and destinations of great interest that are not that far away!

Watch the May 18th segment introducing the 2024 Production of Looking Over the President’s Shoulder: https://www.pbs.org/video/lyles-stations-alonzo-fields-chief-butler-at-the-white-house-rappfy/

James Still’s plays have been produced throughout the United States, Canada, Europe, Australia, South Africa, China and Japan. His plays have been nominated four times for the Pulitzer Prize. Still’s work includes a trilogy of linked plays: The House That Jack Built (Indiana Repertory Theatre), Appoggiatura (Denver Center Theatre) and Miranda (Illusion Theater, Minneapolis); April 4, 1968: Before We Forgot How to Dream (Indiana Repertory Theatre); two plays about the Lincolns: The Widow Lincoln and The Heavens Are Hung in Black (both premiered at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C.); a play for one actor about culinary icon James Beard called I Love to Eat (Portland Center Stage); a play for 57 actors called A Long Bridge Over Deep Waters (Cornerstone Theater Company); Looking Over the President’s Shoulder at theaters across the country; and And Then They Came for Me: Remembering the World of Anne Frank at theaters around the world. His short play When Miss Lydia Hinkley Gives a Bird the Bird was a winner of Red Bull Theater’s Short New Play Festival. Still is an elected member of both the National Theatre Conference in New York City and the College of Fellows of the American Theatre at the Kennedy Center. He received the Otis Guernsey New Voices Award from the William Inge Theatre Festival and the Todd McNerney National Playwriting Prize from the Piccolo Spoleto Festival and has been nominated for five Emmys. He is the playwright in residence at Indiana Repertory Theatre and artistic affiliate at American Blues Theater in Chicago. He lives in Los Angeles.

What does it mean to you to have this play come back to Field’s birthplace?

There is so much poetry and poignancy in this special upcoming production of the play… the idea that Alonzo Fields’ story will be raised up and featured in the place where he was born? It’s emotional for me. The first actor who played Fields was the great late John Henry Redwood. And as part of his initial research for playing the role, John Henry visited Lyles Station and brought home a jar of dirt. He wanted to keep a piece of Lyles Station with him; audience didn’t know it but in the small suitcase Fields used in the play there was a little packet of dirt from Lyles Station! I know David Alan Anderson has visited Lyles Station and the Museum in the old school house as well. Lyles Station has always been an important part of the play — Fields talks about growing up there and clearly it was a place that he carried with him. I do hope audiences will take a moment and consider how moving it is that they are seeing/hearing the play in the place where Fields grew up. Beautiful.

Was there anything you wanted to include but maybe couldn’t find room in the story for?

Of course! That’s almost true with any play that seeks to interact with history… and even more true when it comes to a solo play like “LOOKING OVER THE PRESIDENT’S SHOULDER.” Important to remember — anything I write in a solo play will be spoken by ONE actor and in the case of LOTPS it’s a two-hour play with an intermission. The earliest drafts of the play were about four hours long — Alonzo Fields led a rich and complex life… not only as a witness to so much history happening in the moment, but also in his personal life, in his interior life. But as I continued to rewrite the play I found that it organically revealed what was important for this particular telling. A play like this one is not meant to be an encyclopedia of information — that wouldn’t leave room for an audience to have their own experience as witnesses to Fields’ story. Also: silence is story too. I wanted to honor Fields’ ability to hold his power in silence as well as in spoken language. I never look at this kind of work as what has been left out but rather WHAT IS THE STORY? The story will guide the choices I make as a writer in terms of what drives the storytelling. Again, in my experience this is not unusual but is a particular challenge when turning history into a present-moment experience for audiences.

What surprised you about writing this play?

Everything.

I don’t think I’ve ever started a project thinking I had it all figured out, assuming it would be easy. For me with this play it felt like I was in constant conversation with Fields — I could hear his voice, I could see the way his eyes might scan a room to make sure everything was in order. There were strands of his life that drew me to the project: the universal theme of dreams deferred — Fields wanting to be an opera singer and having to put that dream aside in order to make a living to support his family during the Depression. There was also the idea that Fields was rewarded in his job for being “invisible” — he was noticed only when he was needed, otherwise he was silent on the job. In a way the job required him to be an “offstage character” while on the job at the White House. I wanted to turn that inside out so that he was MAIN CHARACTER… I wanted for him to have his day in the sun, to unlock his voice — his inner life, his struggles, his wisdom, and the relationships he had with the four Presidents he served. I also was drawn to the connection Fields made between “service” and “patriotism” — and how he believed that doing his job beautifully was his art. That thread — of the artist who is in a position of service while in a job that required excellence, leadership, and humility — all of that felt like a dramatic collision of some kind and I wanted to understand all of that more deeply so audiences might understand it too.

Also, it’s important to note that I was still writing the play when 9/11 happened — and on a personal note I want to share that Alonzo Fields was steady and wise company for me during those days and months that followed. The first production at Indiana Repertory Theatre opened two months after 9/11 — and I think that impacted the play in ways I can’t articulate but intuitively know to be true.

When you saw the first run of the play, was there anything about it that struck you especially?

Hmmm. I’ve seen the play several times over the years… I directed the first 7 productions that toured the country. After that I’ve been a guest in the audience many times for several different productions with different actors. But thinking back to the first production in 2001? I remember being struck by how deeply that theme of dreams deferred seem to affect audiences. I saw men weep at the end of the play — something personal about Fields’ story was deeply affecting.

The other thing that I can say is that watching the play I always fall in love with actors again — because it’s such a feat for a single actor to take the stage for two hours and hold an audience in time and space. Mayland Fields (Fields’ second wife and his widow) saw that first production (and a few others as well) and that was always profoundly moving for me because she always felt like watching the play she got to spend a little more time with her husband again. Mayland became a close friend, a grandmother to me. I went to Boston to be with her for her 100th birthday back in 2017! And the actor David Alan Anderson (who has probably done more performances of the play than any other actor) made the trip as well — so it was really special for David and I to be with Mayland for her 100th.

This play is very focused on his White House life and not on his personal life. Was his work just that personal to him, or is that just a choice you made early on?

While it’s true that the play’s focus is on the job, I would argue that the play feels more personal when you’re hearing it from an actor playing Fields on stage. I think that can be harder to feel from just reading it on the page, that idea that all of this story happened to this ONE man — he was a witness and is now (finally) getting to share his story. In many ways your observation is true about Fields in a larger sense — he was not a “kiss and tell” kind of person so the play isn’t that kind of play. Importantly, I never made a choice to steer clear of Fields’ personal life — rather, the structure of the play suggests that what you learn about his personal life will come through the lens of the man who was the Chief Butler of the White House for 21 years. What we learn about his personal life in the play is never an aside or a moment of biography — it’s always in moments supported by something that happens on the job. It’s more nuance and discretion — again, traits that feel perfectly connected to Fields himself.

There’s this line: “Poor men who work their way up sometimes question whether they know what they’re doing.” Did you feel Alonzo was identifying with the presidents?

Well — Fields had a very specific and distinct relationship with each of the four Presidents (and their families) he served. The line you’re referring to is something he observes about President Herbert Hoover and the unfolding disaster of the Great Depression and suggests a kind of empathy with Hoover’s situation. But no, I don’t think Fields thought that about himself — it’s more a musing about the human condition. But there’s also something subtle about his observation when it comes to Hoover in that moment — the idea that even the President of the United States might question whether they know what they’re doing. It’s pulling back the curtain and revealing the humanity of leadership.

In terms of his identifying with the Presidents — Fields is very clear in the play that Harry Truman was the President who respected him most, who saw him as a man and not just as a servant. Again, another connection to Lyles Station: Fields makes the connection that as a Midwesterner, Truman felt familiar to Fields. And again, another time when Fields remembers Lyles Station is in a scene in the play when he’s working during the Truman years.

The play explores art and service; needing a regular job for money and having a dream. As an artist, in terms of being a playwright, were you identifying personally with this theme as you wrote?

In terms of my personally identifying — yes, of course. The connection between art and service is always part of what I do. But again, I wasn’t consciously aware of that while writing the play — it’s Fields’ story, not mine. Part of the mystery and curious experience of writing a play is that feeling of leaning into a character. While writing, the character can seem more real to me than I am to myself! I know that Fields’ profound example of art and service was something that originally drew me to the idea of writing a solo play about him. But even more than that it was a feeling that I wanted him to get to tell his story, I wanted audiences to know Alonzo Fields… I wanted to spend time with this man who was an opera singer who suddenly found himself working in the White House as the Chief Butler.

In your research you got a sense of Field’s character, how do you think his upbringing affected him? Did it in any way prepare him for this special role in a way he wouldn’t have otherwise?

I believe the play makes it very clear that Fields was a man who grew up in a special place, that his parents were special people. I love the section of the play where Fields is standing in the doorway of the Oval Office waiting to serve FDR a meal — waiting to be acknowledged by the President so he can proceed… and in that private moment of silence we hear Fields remembering Lyles Station, recounting what it was like to grow up there… And yes, in terms of preparing Fields for his job in the White House — Fields connected Lyles Station to his early love of music, and it’s his demeanor as an artist and as an opera singer that he later connects to the ways he approached his job as the Chief Butler in the White House. This becomes a deep discovery for Fields in the play — the ways that orchestrating a State Dinner or the Inaugurations or the many scenes behind closed doors where men in power debated politics, the economy, war… that Fields made the connection in his heart between music and doing his job as the Chief Butler with professionalism and precision. Again: Lyles Station is the beginning. Alonzo Fields would always be a man who was born and raised in Lyles Station, Indiana.

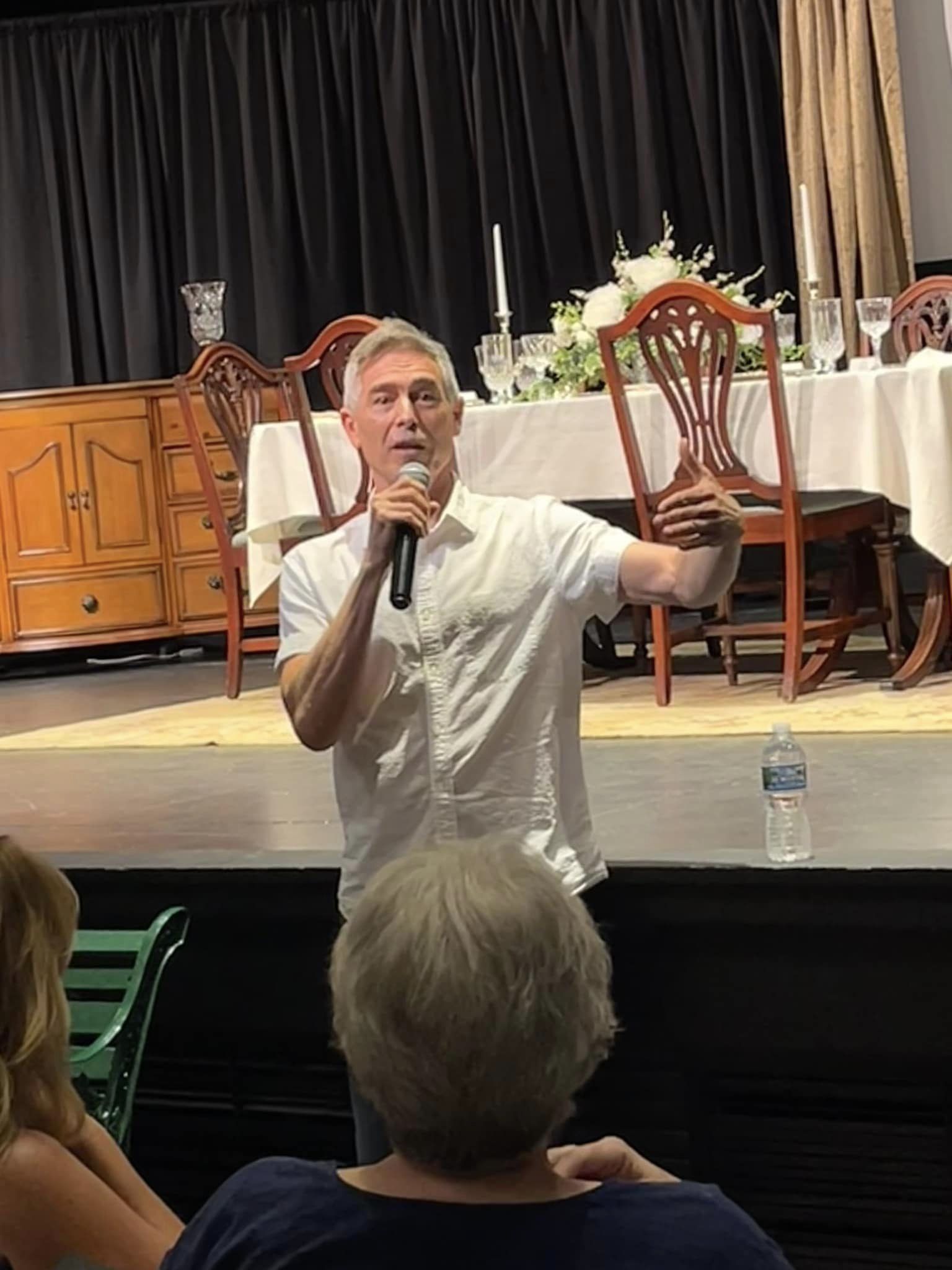

Looking Over the Director’s Shoulder: An Interview with Director Doug Baird

Director Doug Baird is an award-winning actor from San Jose, Calif., where he has appeared in more than 80 productions. He brings his considerable talents to southern Indiana to stage to direct Alonzo Fields’ story, “Looking Over the President’s Shoulder.”

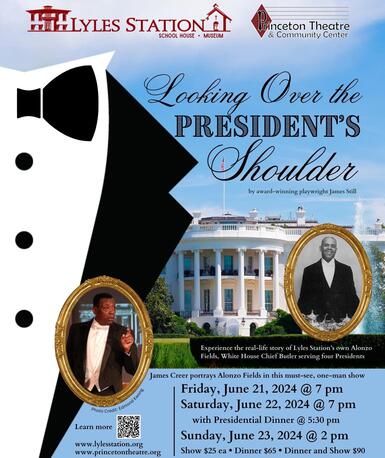

Alonzo Fields, who grew up at Lyles Station, was White House Chief Butler to four presidents over 21 years, before he wrote a memoir recounting his time in service. The play brings Alonzo Fields back home June 21-June 23, 2024, and will be the museum’s third in a “Night at the Museum” series that brings history to life.

Doug has directed the one-man production of “Looking Over the President’s Shoulder” three times, and said every time the team produces this show, it gets better.

His other credits include playing Michael in “I do! I do!,” Madam Lucy in “Irene,” Horace Vandergelder in “Hello, Dolly!,” Julian Marsh in “42nd Street,” Luther Billis in “South Pacific,” Captain Hook in “Peter Pan,” Max in “The Sound of Music,” Jeff in “Brigadoon,” and Hysterium, in “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum,” Colonel Pickering in “My Fair Lady,” Charlemagne in “Pippin,” Hines in “Pajama Game,” Melvin P Thorpe in “Best Little Whorehouse in Texas,” Mr. Parchester in “Me and My Girl,” Herr Schultz in “Cabaret,” and Wilbur Turnblad in “Hairspray,” to name a few.

(If by a few you mean quite a lot. But wait, there’s more!)

His directing credits include, “Baby,” “Annie,” “Mame,” “My Fair Lady,” “Driving Miss Daisy,” “Bells are Ringing,” “Starting Here, Starting Now,” “Tuesdays with Morrie,” “Irene,” “I do! I do!,” “Love Letters,” “Will Rogers Follies,” “Trying,” and “Erma Bombeck: At Wits End” to name a few. (A few more! We could have named 80 productions, so imagine, these are just the highlights.) Doug is a retired Kindergarten teacher, which honestly sounds like a production that a person could never get enough “credit” for.

Doug spoke with our marketing team before Christmas to discuss the heart of this project and why it’s important to continue producing the Alonzo Fields story.

How did you find this project — or did it find you?

I was artistic director for the Tabard Theatre Company here in San Jose and the associate artistic director found it. She said, “I think this is an interesting play, why don’t you read it and let me know what you think.” I fell in love with it. I thought it was a wonderful story. That’s how it came to be.

How did you know James Creer was the right actor?

We didn’t need to have auditions. He was obviously…we wanted James to play the part. He’s very clever. He’s very smart. I knew he would bring this character to life. We’ve mounted it three times and each time it gets better. He brings a lightness to it. He’s very approachable. He’s very kind; he’s very human. He brings that. He makes it very human.

What are the gifts and challenges of staging a one-person performance?

There’s music that’s underscored that’s very special. There’s a projection screen, and when he’s talking about a president, that president’s picture shows up. He talks about the bombing of Pearl Harbor, pictures show up. There’s a picture of him cutting a birthday cake. I did a lot of research to find things that would help tell the story, because it is one person. We also try to keep it moving, he’s not just there telling the story. He’s actually working. He’s going about his duties in the dining room, and stops to talk to the audience. He talks about Marion Anderson, there’s photos of her and we hear her singing. He witnessed her in the White House. It has sounds. A train whistle. You’re in the White House all these years and that makes it feel like home.

I notice this play is very dense with history; is it challenging as a director to deal with a subject that is professional more than personal? People maybe expect things out of plays, things like love stories.

The thing of it is — all this is his perspective. He was in the room where things are happening. When he is there with Winston Churchill in Florida, when he’s in the room with the president and has been up all night, that has a big influence on it. Him being a black American has a huge influence on his work at the White House. That is the love story, it’s his take on history, what he’s witnessing, his relationship with the White House.

Is there any specific characteristic of Fields you think is really important to bring out and not lose?

I keep coming back to the fact he didn’t want to be in service; he wanted to be an opera singer. That’s what he wanted to do. But because he was married, because he had a family to support he went into service … The other thing is — I think about this too—is he an important man in history? I don’t know…I don’t know that he did anything grand, but he wrote a book. He was a witness to history and he wrote it down. That is what gives him his power. He has first hand knowledge of those 21 years.

People sometimes brush off historical pieces as not as relevant, what themes do you think will speak to modern audiences?

A lot of (what Alonzo does) is compromise. You have a job to do and you have to do it within the confines of your job description. But you also have to take care of these people in power. Sometimes we don’t compromise. We don’t do our job. He never gave up. He never said, “screw this I’m out of here.” He wanted to be the best he could be. He strove for excellence.

The play really explores art and service; needing a regular job for money and having a dream. When you look at that tension, do you think Fields had regrets? Is that something the people playing fields or in the entertainment industry highly relate to?

He wanted a career in art, but he had to go into service. That’s certainly what people do now. I have a friend in New York who is auditioning everywhere. But her day job is in service, she works for a catering company. (Fields) wanted a career in art, but he had to go into service. You have to put your goals and dreams on hold.

I think it’s neat that because of Alonzo not getting to live his dream to be an opera singer that every time this is performed another person gets to live their acting dreams in a one man show. Which is really the most a person can do as an actor.

I don’t know if you know how this came to Princeton. James, the actor, went on a road trip, he wanted to know where Lyle Station was. He showed up and it was closing time. Stanley Madison, the curator, said, ‘wait till I close up and I’ll take you in.’ Through their conversation James said, ‘I did “Looking Over the President’s Shoulder,”’ and Stanley said, ‘We always wanted to have that here, at Lyles Station in Princeton.’ James said, ‘I’ll do it. I’d be happy to bring it here.’ That was 2020.”

To get tickets for “Looking Over the President’s Shoulder,” premiering June 21-23, pop by LylesStation.org/Night-at-the-museum/. The show’s run will include a 7 p.m. Friday performance, a dinner theater opportunity Saturday, and a Sunday matinee. Show-only tickets are available, however for Saturday patrons can choose an exclusive, one-night-only White House dinner and show experience.

The museum did sell out of their first “Night at the Museum” performance, and they do expect to completely sell out of tickets to this show, and so the museum recommends getting tickets early.

Meanwhile, patrons can also get an exclusive sneak peek at the subject of the play in the Alonzo Fields gallery at Lyles Station Museum, open Tuesdays through Saturdays 1 p.m. to 4 p.m., or by appointment.

Also follow the journey of Alonzo Fields around town at (link to page where posting.)

This production is a joint effort between Broadway Players and Lyles Station Museum. The play is sponsored by Gibson County Community Foundation.

Realtor and Princeton Community Theatre board member Kelly Bolhofner said the real reason to bring a historical play about Chief Butler Alonzo Fields back to his hometown of Lyles Station and Princeton is that many people don’t know what an influence he had on history.

“It’s not just about bringing together Princeton Community Theater and Lyles Station Museum,” she said. “Bringing Alonzo home gets me teary eyed, that such an important person in the history of Lyles Station, in the history of Gibson County is going to have his story remembered here. A lot of people you say ‘Alonzo Fields’ and they say ‘who?’”

Alonzo Fields, of Lyles Station, was the Chief White House Butler for 21 years through four presidents, the Great Depression, World War II and more.

He witnessed history being made, and wrote a tell-all book, “My 21 Years in the White House,” after his retirement from the White House, then went on speaking tours after his book published.

The book, which billed itself as 21 years of secrets, was not just an early tell-all, but the last book written by a White House member of staff — the White House actually banned memoirs by employees in the wake of the book, requiring all domestic help to sign a waiver.

One paperback cover promised, “No book ever offered such an unusual inside view of White House life–none will leave as many mouths open, as many eyebrows raised.”

The book received generally positive reviews, particularly for its unique perspective on historical events and its insight into the personal lives of the presidents and their families. Fields provided anecdotes, observations, and personal reflections that shed light on the inner workings of the White House and the people who lived there.

That book was part of the research by playwright James Still, who would go on to write “Looking Over the President’s Shoulder,” a one-man play about the life of Alonzo Fields and his dedication to service as an art form.

“This is a good opportunity to show some history of Gibson County, and to talk about why it’s a significant story,” Bolhofner said.

She praised the museum’s efforts to bring the production locally, and added they had requests for tickets before the tickets even went on sale.

The benefit of partnering is the museum’s deep knowledge of Fields’ life, and the way by joining forces the two organizations can reach people who are not in their usual orbit — the museum goers will be drawn in to see Princeton’s historic theater, and their theater regulars will become aware of Lyles Station Museum.

“This brings light to each organization. It’s also a good opportunity for those not familiar with our non-profits to get a taste of what we’re about.

As a Gibson County transplant, she could add that locals don’t always talk about the local attractions.

“I’ve been here since 2016 and I had never been to Lyles Station. Recently I took my grandkids when they were in town,” she said. It was a light day at the museum and they had a private tour from Museum Director Stanley Madison.

She said she didn’t know what they had absorbed, but then was surprised to see their posts on Instagram, quoting Madison and documenting their tour.

“Lyles Station is a significant part of the local history, just like the theater is,” she said.

Since the performance was set, she’s talked with actor James Creer, Director Doug Baird, and Lyles Station organizer Nora Nixon.

“When they pictured us, as a community theater, they thought we were something on the side of the road with flashlights instead of spotlights,” she laughed.

Originally they thought they might have to arrive three weeks before to stage the play, but after the call they had a better understanding of the theater, and its amenities and were able to reduce the time anticipated for staging.

In the meantime, the theater is working hard on things like sponsorships, ticketing, marketing and planning.

To ring in the New Year with the first three sponsors is more than they could ask for, and she added the plan to launch the “where is Alonzo” campaign is going well.

The theater has commissioned a life-sized cut out of Alonzo Fields, and Alonzo will visit local businesses and attractions up until the play premieres to have photo opportunities with locals.

“It’s not only bringing awareness to him and what he means to Gibson County, but also a wider audience. He’ll be at the Indiana Military Museum in Vincennes and the Evansville War Museum among others.”

She said she hopes to introduce a new audience to the Broadway Players. The local company produces four plays a season, and rents out space for special events.

“We’ve lived in our own little bubble for a little while, this year people will see a lot more of us,” she said. “We are a part of the community and want people to see us…We try to maintain that small community.”

The Broadway Players are a volunteer organization, and always need volunteers in the box office, ushers, concession sellers, and actors.

This year they’ll host a February talent show, and four comedies, as well as murder mysteries among other events.

James Creer, a Bay Area actor, hailing from the heart of San Jose, will bring Lyles Station native and Chief White House Butler Alonzo Fields to the stage June 21-23 in a joint production between Lyles Station Museum and Princeton Community Theater that aims to bring home one of the regions most prominent historical figures.

Creer presence to both the stage and solo platforms. With a solid foundation in theater, James is an alumnus of Sam Houston State University and has garnered acclaim for his outstanding performances in a range of roles.

Notable among his credits, James recently appeared in Portland, Ore., with Broadway Rose’s 2023 production of Ain’t Misbehavin’. He took the stage as the commanding General in White Christmas with Children Musical Theatre.

He then mesmerized as Minister Preston in Jive at the Mountain View Performing Arts Center, showcasing his versatility and depth as a performer.

At Hillbarn Theatre, James embraced the role of Horse in The Full Monty, embodying the character with an authenticity that resonated with audiences. His talent shone brightly at Tabard Theatre, where he immersed himself in an array of productions, including I Do! I Do!, Crowns, Looking Over the President’s Shoulder, Tuesdays with Morrie, Driving Miss Daisy, and Stompin’ at the Savoy. James’s dedication to his craft and his ability to inhabit characters from all walks of life is truly commendable.

James’s contributions to South Bay Musical Theatre have been nothing short of spectacular, featuring in productions such as Finian’s Rainbow, Mack and Mabel, Ain’t Misbehavin’, and Guys and Dolls. His performances have added depth and dimension to the characters he portrays, leaving an indelible mark on the local theater scene.

In an unforgettable production of Ragtime by Broadway by the Bay, James left the audience in awe with his captivating performance and compelling stage presence.

Beyond the theater, James has also shared his talent as a guest artist with the

Schola Cantorum of Los Altos, showcasing his musical abilities and enriching the local

choral scene.

He’s a familiar face at the San Jose Jazz Festival, where his charismatic

performances have added a unique flavor to the vibrant music scene.

James Creer’s journey as a performer is a testament to his unwavering dedication,

his remarkable range, and his ability to leave a lasting impact wherever he goes.

With his captivating performances and charismatic stage presence, James will bring Alonzo Fields back home.

He sat down with interviewer Janice Barniak Dec. 13 to discuss this project:

Do you feel like you’re channeling Alonzo, or do you as a person already have a lot in common with him?

It’s a little bit of both. As I began to read about Alonzo, as I began to understand his background and how he became who he was, oftentimes our career paths we choose are not what we wind up with.

Like him, I directed a choir in church. Reading that about him, and going and visiting the space helped me focus on how real he was. I’d try to go in my mind on every path he talked about traveling and visit that space and be in that moment. It really takes concentration and time to try to develop that.

How would you describe Alonzo as a person?

Alonzo was resilient in his life. He did not give up because of the obstacles put in place. He was determined to be that opera singer he wanted to be. It’s just that circumstances never fully allowed him to accomplish that. Resilience was one of his huge qualities.

It’s not as if he’s a victim of his circumstances; he’s adapting.

I don’t think he thought of himself as pushed down at all. Remember it was the Depression, a lot of people were out of work. His boss died, and just by his meeting the first lady and observing his qualities, his stature, and how he performed his duties–that left an impression on her. He took every step very intentionally. By doing that, when you release yourself to explore possibilities you didn’t think of it can take you places that are better off for you.

What were the challenges in finding this character in a play that is largely about his professional career?

In this play, for me to portray him, I did a lot of research. I watched videos where he was talking just to see his demeanor and how he would answer questions. He had some comedy within himself. He was a funny character, combined with seriousness. Looking at the short videos I could find, then I talked with the writer James Still, because he had the opportunity to talk to Alonzo’s wife so many times and to read through so many documents.

I’m letting go of who I am and at the same time, some of that may apply to me also.

To be honest, I’m still doing it. Even now, I’m making it better. I’m embodying him even more.

So this is a path; your third stop on a much longer journey.

Most definitely.

What makes you want to keep portraying the same character? Do you find something new in each performance?

The first time, I was learning this to perform this show. The second time, I did it, I was revisiting the script and discovering things I overlooked the first time, because the first time I was intense into making sure I had the lines right. Then you dive deep into the character, the wife, the child the second wife, the descendents. I’m like, “if I was the great-grandson of him, how much would I be like my great grandfather.” There’s tons of things that go through your mind. He was a mentor to the younger people who came to the White House, who looked up to him. Then I think about the children in theater who look up to me when I go to children’s musical theater for shows. I look at Alonzo and I marvel at him. Especially his resilience. He helps me even in my day-to-day life, when I come to things I think are absurd.

I wish he could know what came out of him writing this book. It was the last book a servant was allowed to write from the White House. I wish there was a better word than servant.

Honestly, that does really embody the character and the time though. These words need to be used. So me, as an actor, can understand, “I didn’t have have a voice there. I was the servant. I was seen; I was there to provide a service, and that was it.”

You visited Lyles Station before this play was planned. Tell me about that visit.

What happened was, in 2020, they closed everything down and the world came to a halt. I am not a cocooned person; it’s very hard for me to stay still. I thought, “why not take advantage of this time and take this cross country trip across the US I’ve been wanting to do forever?” I call it my landscape tour. So I left San Jose on Sept. 3 and headed out to go as far as Atlanta, which I did, then went to the coast a little bit and came back across. Well as I was doing that, my plan was at least to go to Lyles Station. It was still there. I wanted to see it. When I got there I was pleasantly surprised because the church Alonzo’s father directed was still there. To be on that property and walk that — to go through the museum and Mr. Stanley gave me the tour as he was working and repairing things. I told him I wanted to do it because I was in the show. He’s like “oh yeah! We always hoped it would be done here. I had no intentions at that time. He said they had a plan at one point, but the person passed away, and they just haven’t been able to get it done. I told him, well, if there’s an interest still when all this (the pandemic) is over I’d be delighted to do it. That’s how it came about.

Was there anything that surprised you about that trip or added context?

Well, the real thing is to find Stanley, a descendent of Lyles Station, with all he knows. That was a treasure all on its own. Because we tend to leave places when they get desolate. Just knowing he had personal knowledge as a descendent brought a different look, like “can I bring this man back to where people will understand his journey and appreciate the history he left behind for Lyles Station.”

What are the gifts and challenges as a one man show?

When they asked me if I would be interested in doing a one man show, I’m like “oh just me? How exciting.” Of course, then you get this book with 60 pages of lines, and it’s “what was I thinking? Will I ever learn it?” It wasn’t as hard because I had an amazing director. Doug kept me calm at times when I thought, this is never going to work.

Alonzo never got to be the performer he wanted to be but through him, all these actors playing him, live their dream. I wonder if actors who play with Alonzo identify with him as far as serving?

I do. I grew up in a small town of Henderson, Texas. I loved theater, but my parents were like, “that’s fine, you can like doing that, but no one gets paid for being silly onstage.” It was just a taboo, no, you can’t do that. I was just going to teach music. I played piano for church choir, did church choir, went to college and worked in finance for awhile. I worked for the state attorney general for Texas, then had an opportunity to come to California–I’d left my passion. Then someone asked me to participate in a theater production. I said sure, and with that the bug hit, and I’ve been doing this since. I just appreciate bringing that art to life. It’s so different on the stage live tan on television. It allows the individual to imagine. You’ve been transported to a specific place and time.

Is there anything you hope the audience walks away with from this performance?

As we take them back in time, there’s all these characters I mimic as I take them back with this show. There’s so much he saw that he wrote down because he couldn’t discuss it with everybody. It lets the audience take a peek at things that happened at the White House from a servant’s perspective, not from the president’s perspective or some other dignitary. I think that’s award worthy by itself because it’s so rare. I hope they take away the real-ness of who these people are. I hope they take away the real-ness of what still exists. I hope they take away an awareness that they can have an impact on our country as a whole.

Did you know that when President Franklin D. Roosevelt took over the White House salaries of everyone who worked there were cut 25 percent to fulfill a campaign promise?

Lyles Station native Alonzo Fields wrote in his book “My 21 Years in the White House,” that during the Hoover administration servants made $60-90 per month, ($1,461.66-$2,192.49 today) plus three meals for butlers and cooks; two for other servants. Paychecks were reduced when the Roosevelts moved in.

“There was too much work for even the head man to stand around and pose,” Fields wrote in his book.

The push to reduce government spending went all the way down to the dining utensils. Servants didn’t have enough flatware for all the courses, leaving them to do the dishes in order to have enough forks to serve dessert.

To learn more about this, Alonzo Fields, or President Roosevelt, pick up tickets to Looking Over the President’s Shoulder, a play Lyles Station and Princeton Theater are organizing in June, or stop in during regular museum hours to see the Alonzo Fields exhibit at Lyles Station.

Museum seeks missing journals of Lyles Station native in preparation for performance

Walking up to Lyles Station Museum, a museum housed in a former two-story schoolhouse, is humbling. In one room you see the simple blackboard and schoolroom where the students would learn 16 spelling words per day; in a gallery — quilts, medals, and recognition from Lyles Station alumni, sit aside artifacts of the pioneer farming life people in the all-black Indiana settlement led.

Lyles Station was a haven for those fleeing persecution, a stop on the Underground Railroad, and this summer expects hundreds of guests for their Juneteenth celebration that will feature a three-day run of a play about one of their most famous locals, Alonzo Fields, former Chief White House butler to four US Presidents.

But while their gallery celebrating Alonzo Fields is excellent, and includes a copy of his tell-all book, “My 21 Years in the White House,” there is something missing, a mystery lost to history if you will.

The museum only has five of what would have been at least 20 diaries of their native son. The rest they would love to find before the crowds they expect for the Fields homecoming.

To rewind, after Fields left butler service, he wrote his book based on his journals. He did a book tour of the country, and his book was eventually the basis for “Looking Over the President’s Shoulder,” a one-man play dramatizing the large historical moments of Fields’ life and his take on them during his time in the White House.

The Fields exhibit at Lyles Station features magazines Fields was in, his diaries, invitations and photos, among other items.

“We put this (exhibit) together with the understanding that Fields was a man of character,” Museum Director Stanley Madison said. “He could tackle things that seemed impossible.”

That was not just as a butler but as a man experiencing peak segregation.

“This lady,” Madison gestures to a white maid, “and this lady–” he points to a black maid, “–could not clean in the same room.”

Blacks and whites couldn’t ride together in the service elevators, for example, so in Fields’ responsibilities he had to keep a running mental load that juggled the issues of segregation while getting all the work done.

This was at a time when there were no downtown movie theaters that would allow black people to view movies, and the one playhouse that allowed blacks to attend were the burlesque shows, and at those, they had to sit in the upper gallery.

But times were changing, and Fields changed with it. He adapted to each president’s requirements.

During the Hoover administration, for example, the servants were supposed to be completely unseen, to the point there were designated closets for workers to jump into when the president or first lady were about to walk through.

Compare that to the Roosevelt administration, when Fields was asked what he thought about policies.

“They were sitting out at the chestnut tree behind the White House,” Madison recalled during a tour of the Fields exhibit. A commanding officer gestured to Fields, who was serving, and told the group the man shouldn’t be privy to the confidential security information. Roosevelt disagreed. “Put some numbers behind Fields’ name. There. He’s just become an agent.”

Fields kept a daily diary of his time in the White House, which he used to write his book, and the museum has five of these diaries as the centerpiece of their display. Fields’ controlled scrawl.

The page in the exhibit currently sits on Thursday, Jan. 8, 1942.

“Tonight the Prime Minister (Winston Churchill) asked me for a second Scotch and soda after Champagne with dinner, and three glasses of brandy, including sherry. He says, ‘You know I have a heavy burden on my shoulders such as fighting the war, so give me another Scotch and soda; it helps to keep up the morale…’”

While justly proud of their Fields exhibit, the museum is looking for the rest of Fields’ diaries to complete their set. Mayland Fields, the widow to Alonzo, gave the museum five tomes that are the current centerpiece of the Fields exhibit.

Efforts to find the other missing diaries have not been fruitful.

The museum checked with the Truman Institute, because Truman and Fields were close friends, but that exploration didn’t turn up the missing diaries.

Madison likens the journals to a trail of history.

“I see the story of Fields as a young man from a small town taking it on his shoulders to be the best of the best he could possibly be,” Madison said.

If anyone has a tip to help the museum in locating the missing Alonzo Fields journals, call 812-385-2534. The museum is open 1 p.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Saturday and by appointment.

To buy tickets to “Looking Over the Presidents Shoulder” go to www.lylesstation.org or www.princetontheatre.org

In “My 21 Years in the White House” Chief White House Butler Alonzo Fields, who was from Lyles Station, just outside Princeton, talks about private moments with presidents, things like FDR receiving the news of Pearl Harbor, Hoover battling the Great Depression and an assassination attempt on Truman.

What he doesn’t talk a lot about is his own personal life with his wife, his own politics, how he judged presidential decisions or his lived experiences of segregation.

Some of those he does address in later interviews. In an interview with Washington University for a documentary on the Great Depression, he talked about segregation.

Fields remembered that on the bus trip to the White House, he accidentally went into an unmarked white restroom. The restroom was unmarked, but the hostility he felt from those inside was not. When he came out, a fellow person of color indicated a separate, lower quality restroom behind the rest stop.

The first thing that struck him in Washington, he said, was right in the White House. He was surprised, initially, that white help were segregated from people of color doing similar work.

“There was one department store, blacks weren’t welcome at all…You’d stand around before you’d be served,” he remembered, adding there were places black Americans couldn’t get a line of credit.

There were movie theaters downtown, but none of them would serve people of color; the only show both people who were white and people of color could attend was a burlesque show. (Women dancing.) The people of color were relegated to the upper level of the theatre, however.

Certain theatres had certain days a person could go with an all black cast.

Alonzo Fields was born in Lyles Station, Ind., and grew up in an era marked by racial segregation and discrimination. Despite the challenges, Fields pursued education, and ran a grocery store before becoming butler to an academic home that let him pursue his passion to become a classically trained opera singer.

He was set to have his debut, when the death of his employer left him without a job. He’d met Mrs. Lou Hoover, wife to President Herbert Hoover, at his employer’s home. She remembered him, and he was offered a position in the White House in 1931.

It was early in the Great Depression, so he felt blessed to have a job, and intended to go back to opera singing after the winter was over. That winter lasted 21 years.

Fields, however, was known for his lightheartedness, and developed a passion for hospitality and service.

Fields’ exceptional professionalism, attention to detail, and dedication led to his eventual promotion to the position of Chief Butler, making him the first Black man to have that role.

During his time in the White House, spanning administrations from Hoover to Eisenhower, Fields witnessed history, serving everyone from queens and princesses to members of the presidents’ families.

He was chosen for special missions by each president, and gave input to them when asked. He also saw numerous moments of global importance, from the bombing of Pearl Harbor to the Korean War.

Fields’ memoir, titled “My 21 Years in the White House,” sheds light on the behind-the-scenes happenings, offering a unique perspective on the personal lives of the presidents and their families, as well as the significant historical events that unfolded during those years.

His tenure in the White House not only exemplified his exceptional skills and broke racial barriers.

He stands as a symbol of dignity, professionalism, and perseverance in the face of adversity.

Alonzo Fields passed away on March 22, 1994, leaving behind a legacy of excellence in service and an enduring contribution to American history.

In an unforgettable theatrical journey, Princeton Community Theatre and Lyles Station Museum present “Looking Over the President’s Shoulder,” a compelling production that invites audiences into the life of Alonzo Fields, the chief butler at the White House during the administrations of Hoover, Roosevelt, Truman, and Eisenhower, and a native to Lyles Station, Ind., just outside Princeton.

“Looking Over the President’s Shoulder” invites you to be moved by the enduring lessons of humor, integrity and fortitude.

Performance Details:

- 7 p.m. June 21

- 7 p.m. June 22

- Presidential Dinner Option starts at 5:30 p.m.

- 2 p.m. June 23

- Princeton Theatre

- Tickets: Available at LylesStation.org/Events

For media inquiries, interviews, or press passes, please contact Nora Nixon at 812-385-6941

Which Local Man was once sent on a secret mission for President Franklin Roosevelt?

On Jan. 3, 1942 President Franklin Roosevelt gave Lyles Station native Alonzo Fields, (who came from right outside Princeton and went on to become Chief Butler at the White House) notice that he was to gather a crew immediately for a secret mission, destination unknown. Every person was to pack their bags for 10-15 days, and they were told they could give no information to their families.

“Those who needed tools, I told to get their tools, to answer no questions and to get out of the house as quietly as possible,” Fields later wrote in his book about his service.

At 2 p.m. Sunday, Jan. 4, a Secret Service member picked up Fields and him and his crew to Washington’s Union Station to catch a train. Only Fields knew the destination and was instructed to read his instructions and destroy them.

They would get off at Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and be met by a Secret Service officer, and taken to the home of a state department relative. They had no idea who they would be caring for, but the Secret Service said to prepare for 15-20 people for dinner; it was 2 p.m.–dinner was at 8 p.m.– and Fields ended up using his own money to buy food and alcohol for the guests.

When the guests arrived, it was Prime Minister Winston Churchill and his naval aide, Scotland yard chief, and physician among others.

It was the height of World War II, only days before 26 Allied countries had signed the Declaration by United Nations. Two days after this arrival, Roosevelt would announce more aid to Britain in his State of the Union Speech. Chief Butler Alonzo Fields was on the front lines as history was made.

To learn more about secret White House workings, Alonzo Fields, or President Roosevelt during World War II, pick up tickets to Looking Over the President’s Shoulder, a play Lyles Station and Princeton Theater are organizing in June, or stop in during regular museum hours to see the Alonzo Fields exhibit at Lyles Station.

Show Reviews

“This one-man show is at once warm, thought-provoking, and inspiring. I cannot recommend this play strongly enough. It is a timeless story for all ages, a pure joy to see, and a story and performance you will remember long after the curtain falls.”

– TriCities.com

2022 Production of

Fugitives and Heroes – Experience the struggle for freedom on the Underground Railroad

Freedom or Captured?

In a nation on the road to Civil War, the Fugitive Slave Act ignites a powder keg that intensifies north and south divisions and magnifies the dangers for the enslaved and those who help them. Meet 10 historical figures as they make daredevil escapes, face unfathomable challenges, and continue to pave the road on the Underground Railroad with their courage and blood.

Lives, a Nation, and True Freedom in the Balance

A Night at the Museum

Get Directions

953 N. County Road. 500 W.

PO Box 1193

Princeton, IN 47670